How do animals choose their mates? Dr. Maddie Girard and Dr. Damian Elias were pretty sure they knew what female peacock spiders found sexy—it had to be the red.

Found throughout Australia, these tiny jumping spiders have excellent vision, and instead of a making a web, they sneak, climb, and pounce to catch their food. As their common name suggests, when a male peacock spider finds a female, he raises his abdomen, unfurls his fan-like tail, and, while singing through vibrations in the ground, shakes his tail in a thrilling dance performance. These eye-catching tails are usually decorated with brilliant reds, perfect for wooing females.

Since 2009, Girard and Elias have been studying how and why peacock spiders’ displays have evolved. In general, biologists think that in some species, females find males with elaborate displays attractive, and by mating with those males, females have selected for these sexy traits over evolutionary time. In 2015, Girard discovered that, when choosing whom to mate with, females seemed to care more about a male’s appearance than his vibrational song. So what exactly made male peacock spiders look so sexy?

One clue was relatively obvious: “[Red markings are] one of the things that makes [peacock spiders] special,” explains Elias. While red coloration is rare amongst spiders, the majority of the 65 described species of peacock spiders have males with red patterns. If females choose a mate based on how red he was, this could explain why red is such a common feature of male displays.

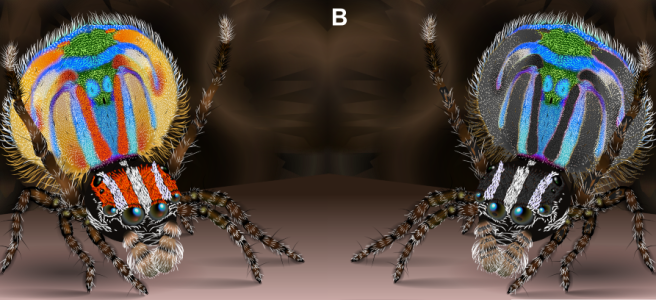

Girard and her colleagues tested this idea in their latest study, published in 2018 in the journal Behavioral Ecology. Focusing on one species, Maratus volans, they compared how likely females were to mate with a courting male with and without his red coloration. Girard used an array of customizable colored LEDs to change how males appeared to females. By turning off only the red LED, there would be no red light to reflect off of males, and their previously bright red patches would now appear to be very dark or black.

Without their red coloration, mating rates plummeted to nearly half of what they had been when males’ red colors were visible. Girard’s suspicions were confirmed. There was something special about those brilliant reds that females couldn’t resist, and males had evolved to cater to that desire. No red, no mating.

Elias recalls feeling nonplussed. “Yeah, red animals like red. Okay, great, but..?” Nothing groundbreaking, but hey, at least it made intuitive sense.

Still, before they could wrap up their study, Girard and her team had to deal with a small issue. When Girard had cut out the red light, this also decreased the total amount of light on the stage. So, other parts of the males’ tail fans might have appeared to be slightly darkened as well. On the off chance that that mattered, they turned up the brightness of the remaining LEDs to compensate, and tested more pairs of spiders.

And then, Girard’s all-too-tidy explanation fell apart.

Mating rates jumped back up to normal—even though there was no way females could be seeing any red when they looked at the courting males. The red LEDs were still off. But the females didn’t care. No red, yes mating.

In Maratus volans, a species where by all appearances males evolved red coloration to appeal to females, females did not actually care about the color red.

“It was a complete surprise,” says Elias. “We expected it to be just a simple control [experiment] that wouldn’t say anything new.” But the scientists were now forced to rethink their assumptions about these animals.

Eventually, Girard and her team came up with a possible explanation. Females could be choosing males based on the overall pattern and design of their fans—not on any one color—and might be using contrast to do so. Contrast is a measure of how different two nearby objects are in either their color or their brightness. Eyes, including our own, find the “edge” where one object ends and the other begins by using contrast. And finding edges is the critical first step to identifying shapes and patterns.

Female peacock spiders seem to be able to use both types of contrast when looking at males. In normal, bright light, females can make out the patterns on a male’s fan because each part of the pattern is a different color. However, some male colors are also brighter than others. So, females could use this difference in brightness to make out the patterns, even without seeing red, as long as there was enough light overall.

Girard now thinks that males’ red coloration only matters in the sense that those reds are different from the adjacent blues in the fan. If females care about seeing certain shapes and patterns, patterns made out of red and blue are easier for her to see and evaluate.

We humans are visual animals—for many of us, our eyes are the primary way we interact with the world. But our eyes come with their own built-in assumptions; we often think that certain colors, shapes, and patterns are more important than others. After all, we are wired to think that red is inherently sexy; many studies have found that people are more attracted to romantic prospects when they are wearing red, or even just standing in front of a red background. We are not even aware of this effect when it is happening, which might be why it is easy for us to subconsciously assume that other animals work the same way. ‘’Of course female peacock spiders should care about how red males are. Look at the males; they’re covered in red!’

But the last common ancestor of humans and peacock spiders lived 800 million years ago. Our eyes and brains have evolved completely independently. What we cannot help but notice on a potential mate, they apparently don’t interpret in the same way.

To truly understand what is going on in the world around us, we can’t just trust our senses. Rather, we need to overcome our inherent biases. Thankfully, we’ve developed a set of tools to do just that. As Elias puts it, “the reason that the scientific method is so powerful is that it allows you to divorce yourself from your preconceived notions of how animals should work.”

So what is the next notion up for testing? Well, isn’t it obvious? It’s clear what female peacock spiders find sexy—it has to be the pattern.

—

I would like to thank Dr. Damian Elias for agreeing to be interviewed for this piece. I also reached out to Dr. Maddie Girard, but did not receive a response. To learn more about Dr. Girard and her work, you can visit her website. To learn more about the Elias Lab’s work on jumping spider communication, visit their website.

I am a PhD student studying how animals use colors, patterns, and movement to talk to each other. You can learn about my research and meet more cool spiders at www.spiderdaynightlive.com, @SpiderdayNight on Twitter , and @SpiderdayNightLive on Instagram.

—

Literature Cited

Elliot, A. J., & Niesta, D. (2008). Romantic red: Red enhances men’s attraction to women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1150-1164.

Elliot, A. J., Niesta Kayser, D., Greitemeyer, T., Lichtenfeld, S., Gramzow, R. H., Maier, M. A., & Liu, H. (2010). Red, rank, and romance in women viewing men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(3), 399-417.

Girard, M. B., Kasumovic, M. M., & Elias, D. O. (2011). Multi-modal courtship in the peacock spider, Maratus volans (OP-Cambridge, 1874). PLoS One, 6(9), e25390.

Girard, M. B., Elias, D. O., & Kasumovic, M. M. (2015). Female preference for multi-modal courtship: multiple signals are important for male mating success in peacock spiders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1820), 20152222.

Girard, M.B., Kasumovic, M.M. and Elias, D.O., 2018. The role of red coloration and song in peacock spider courtship: insights into complex signaling systems. Behavioral Ecology, 29(6), pp.1234-1244.

One thought on “Seeing red in a new light: Peacock spider courtship defies our human assumptions”